Two Dystopias

In “The Parable Of the Sower”, Octavia E. Butler, writing in the early 1990s predicted a dystopian California in the period 2024 through 2027. How accurate was her prediction? We can ask the same question about J.G. Ballard’s “The Drowned World” written in the 1960s. Ballard does not give us a date for his drowned world, but it seems not too far in the future. All of the technology in his novel is contemporary to the 1960s.

The authors agree on some things, all of which we see in 2024. One is global warming and its attendant rise in ocean levels. The other is mass, global migration driven not by poverty or violence, but by a changing climate. In both novels, the migration flows north or south to cooler climes.

Octavia E. Butler was right about the warming and drought. What has not yet happened in California is the breakdown of civilized society. Any cities or towns that haven’t been deserted are walled to keep out the violence in a dangerous, lawless Wild West. Things are shaky even inside the walls. Public services like police and fire are undependable and corrupt; with officers that are not much more than shake-down artists. There is an ever-present danger that violent and desperate gangs from outside the walls will break in and burn, steal, kill, rape; destroy the town; and leave it a smoking ruin. There are only two things in the book that one can’t easily see coming true. One is an inherited condition called hyperempathy syndrome in which the sufferer feels the emotions, pains, and pleasures of others. Lauren, the protagonist, is a sufferer, called a sharer, and even as a child she bled when she saw others bleed.

The other thing we don’t see in today’s California is the use of pyro, a highly addictive drug that gives its users pleasure when burning something; anything including people. Wildfires are a problem, as is the case in California today. They are a more serious problem in Butler’s California because of pyro. Many of the people outside the walls are in the grip of the drug. People get hooked on setting and watching fires whether of buildings, forests, animals, or humans.

People are setting fires to do what our arsonist did last night—to get the neighbors of the arson victim to leave their own homes unguarded. People are setting fires to get rid of whomever they dislike from personal enemies to anyone who looks or sounds foreign or racially different.

They’ll burn everything, . . . They won’t stop until they’ve used up all the ‘ro they have. All night, they’ll be burning things. Things and people. . . . They hate everybody who isn’t them. They would have sold my Tori [a very young daughter] to get some more ‘ro.

But it’s the fire that holds our attention. Maybe it was started by accident. Maybe not. But still, people are losing what they may not be able to replace. Even if they survive, insurance isn’t worth much these days.

As Butler wrote, California is warmer and prone to catastrophic drought. Sea levels are rising. Many of California’s flat, sandy beaches are just a memory. So are the houses and businesses that used to sit on the beaches.

Like coastal cities all over the world, Olivar [a town] needs special help. . . . The whole state, the country, the world needs help . . .

Water is in short supply, sold on the free market, and expensive. There are no working, municipal water systems. People buy bottles or other containers of water directly from the seller.

Today we stopped at a commercial water station and filled ourselves and all our containers with clean, safe water. Commercial stations are best for that. . . . There aren’t enough water stations. That’s why water peddlers exist. Also, water stations are dangerous places.

We don’t see the widespread, social breakdown in today's California. In Butler’s California, cities and towns are either walled as in medieval times or destroyed and abandoned. Poverty and homelessness are widespread. The poor and abandoned are helpless to defend themselves against the lawless bands that roam outside the walled towns and cities. Masses of people are moving north on foot via the roads and highways where there are no vehicles. They are moving north in search of cooler temperatures and the chance to find a paying job. Cities walled themselves in so “they don’t have to risk going outside where things are so dangerous and crazy.”

The neighborhood wall is a massive, looming presence. . . . but my stepmother is there, “City lights”, she says, “Lights, progress, growth, all those things we’re too hot or too poor to bother with anymore.”

All the adults were armed. That’s the rule. Go out in a bunch, and go armed.

Crazy to live without a wall to protect you. Even in Robledo, [Lauren and her family’s home] most of the street poor—squatters, winos, junkies, homeless people in general—are dangerous. They’re desperate or crazy or both.

There isn’t much pleasure around these days.

In L.A. some walled communities bigger and stronger than this one just aren’t there anymore. Nothing left but ruins, rats, and squatters.

Internal migration is underway with people moving north away from the heat, drought, and lawlessness. States are closing their borders to keep out the migrants.

. . . the freeway crowd is a heterogeneous mass—black and white, Asian and Latin, whole families are on the move with babies on backs or perched atop loads in carts, wagons, or bicycle baskets, sometimes along with an old or handicapped person. Other old, ill, or handicapped people hobbled along as best they could with the help of sticks or fitter companions. . . . People get killed on freeways all the time.

So many people hoping for so much up where it still rains every year, and an uneducated person might still get a job that pays in money instead of beans, water, potatoes, and maybe a floor to sleep on.

Highway 101 [is now] a river of the poor. A river flooding north.

“Where are you going now?” I asked.

“North.” He shrugged.

“Just anywhere north or somewhere in particular?”

“Anywhere where I can be paid for my services and allowed to live among people who aren’t out to kill me for food or water.”

Company towns are springing up:

Workers make things for companies in Canada or Asia. They don’t get paid much, so they get into debt. They get hurt or sick, too. Their drinking water’s not clean and the factories are dangerous—full of poisons and machines that crush or cut you. But people think they can make some cash and then quit. I worked with some women who had gone up there, taken a look, and come back. . . . The workers are more throwaways than slaves. They breathe toxic fumes or drink contaminated water or get caught in unshielded machinery. . . . It doesn’t matter. They’re easy to replace—thousands of jobless for every job.

Here’s an issue that’s been around for a long time.

All that money wasted on another crazy space trip when so many people here on earth can’t afford water. . . . The cost of water has gone up again . . . costs several times as much as gasoline. But, except for arsonists and the rich, most people have given up on buying gasoline.

Politicians and big corporations get the bread and we get the circuses. . . . Most people have given up on politicians. After all, politicians have been promising to return us to the glory, wealth, and order of the twentieth century ever since I can remember.

Butler summarized the general situation in California and elsewhere in 2027:

But everything was getting worse: the climate, the economy, crime, drugs, you know. I didn’t believe we would be allowed to sit behind our walls, looking clean and fat and rich to the hungry, thirsty, homeless, jobless, filthy people outside.

This was farm country. We’d passed through nothing for days except small, dying towns, withering roadside communities and farms, some working, some abandoned and growing weeds.

Humans will survive of course. Some other countries will survive. Maybe they’ll absorb what’s left of us [the U.S.]. Or maybe we’ll just break up into a lot of little states quarreling and fighting with each other over whatever crumbs are left. That’s almost happened now with states shutting themselves off from one another, treating state lines as national borders.

You know, as bad as things are, we haven’t even hit bottom yet. Starvation, disease, drug damage, and mob rule have only begun.

There are always a few groups of homeless people and packs of feral dogs living out beyond the last hillside shacks.

“There’s cholera spreading in southern Mississippi and Louisiana,” I said. “I heard about it on the radio yesterday. There are too many poor people—illiterate, jobless, homeless, without decent sanitation or clean water.”

Tornadoes are smashing the hell out of Alabama, Kentucky, Tennessee, and two or three other states. Three hundred people dead so far. And there’s a blizzard freezing the northern midwest, killing even more people. In New York and New Jersey, a measles epidemic is killing people.

A main theme running through the book is the question of what is God and what is religion. Can there ever be a religion that doesn’t turn bad?

So what is God? Just another name for whatever makes you feel special and protected?

Is it a sin against God to be poor? There are fewer and fewer jobs among us, more of us being born, more kids growing with nothing to look forward to. One way or another, we’ll all be poor someday. [p. 15]

Is there a God? If there is, does he (she? it?) care about us?

Lauren is creating a new religion that she has decided to call Earthseed. The central tenet of her developing religion is that God is change, and change is inevitable.

My God doesn’t love me or hate me or watch over me or know me at all, and I felt no love for or loyalty to my God. My God just is.

What did Butler get right? The warming and drought, the wildfires, and the migration. What wrong? There is no drug like pyro; no syndrome like hyperempathy. California has not yet experienced the social breakdown that Butler depicts.

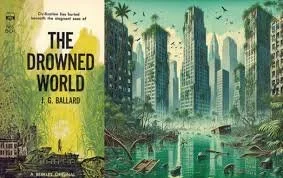

“ The Parable Of the Sower” depicts a plausible future. J.G. Ballard’s “The Drowned World” is less plausible. Written in 1962, the novel does not specify when it takes place. It doesn’t seem too far in the future because there is no futuristic technology. The world has been devastated by global warming. The warming has caused unimaginable flooding. I don’t think any current predictions of flooding picture anything as dramatic as in this book. The action centers on London. When the protagonists arrive by boat, they don’t recognize where they are. The city is flooded up to the seventh floor of buildings. Many are completely underwater. They realize it’s London when a man who lived in London before the deluge recognizes some locales that are now underwater.

The warming and flooding happened quickly; within the lifetime of one of the book’s older characters, the one who remembered London, his home, as it existed before the high water. This is the London of “The Drowned World.”

Giant groves of gymnosperms stretched in dense clumps along the rooftops of the submerged buildings, smothering the white rectangular outlines. Here and there an old concrete water tower protruded from the morass, or the remains of a makeshift jetty still floated beside the hulk of a collapsing office block, overgrown with feathery acacias and flowering tamarisks. Narrow creeks, the canopies overhead turning them into green-lit tunnels, wound away from the larger lagoons, eventually joining the six-hundred-yard-wide channels which broadened outwards across the former suburbs of the city. Everywhere the silt encroached, shoring itself in huge banks against a railway viaduct or crescent of offices, oozing through a submerged arcade like the fetid contents of some latter-day Cloaca Maxima. Many of the smaller lakes were now filled by the silt, yellow discs of fungus-covered sludge from which a profuse tangle of competing plant forms emerged, walled gardens in an insane Eden.

The warming is severe; like the flooding, greater than any current predictions. In London, the daytime temps reach 140° F to 150° F.

. . . the thermo-alarm on the balcony now registered a noon high of one hundred and thirty degrees—and the enervating humidity made it almost impossible to leave the hotel until after ten o’clock in the morning . . .

The noon temperature of a hundred and fifty degrees had drained all energy from him. . .

Temperatures at the Equator are up to one hundred and eighty degrees now, going up steadily

It’s not very plausible that humans could function in temperatures that high. According to Popular Mechanics

Externally, the upper limit of the human body's thermoneutral zone—the ambient temperature range in which the body can effectively maintain its temperature and equilibrium—likely falls somewhere between 104 and 122 degrees Fahrenheit **

A large percentage of the world’s population has died. The rest have sought refuge in the only areas still habitable, above or below the Arctic and Antarctic Circles.

. . . waves of refugees moving northward during the past thirty years in their power boats and cabin cruisers.

. . . most of the people still living on in the sinking cities were either psychopaths or suffering from malnutrition and radiation sickness.

The tacit assumption made by the UN Directorate—that within the new perimeter described by the Arctic and Antarctic Circles life would continue much as before, with the same social and domestic relationships as before, by and large, the same ambitions and satisfactions—was obviously fallacious, as the mounting flood-water and temperature would show when they reached the so-called polar redoubts.

Most mammals and birds seem to have disappeared; I assume they went extinct, although the book’s final paragraph mentions giant bats. Reptiles have proliferated; especially crocodilians and iguanas. The earth is covered in water, silt, and rampant vegetation that harks back to the era of the dinosaurs.

an attack by two iguanas on the helicopter the previous night . . . [must be big iguanas] . . . huge predatory insects . . .

What I’ve written so far is understandable, extreme but understandable. No mention is made of humankind’s contribution to global warming.

A series of violent and prolonged solar storms lasting several years caused by a sudden instability in the Sun had enlarged the Van Allen belts and diminished the Earth’s gravitational hold upon the outer layers of the ionosphere. As these vanished into space, depleting the Earth’s barrier against the full impact of solar radiation, temperatures began to climb steadily.

The warming melted glaciers and millions of acres of permafrost. The rising sea levels altered oceanic currents in a way that contributed to the warming.

A peculiarity described in the book is a sort of psychological and genetic regression of humans back to when they or their non-human ancestors lived in a warmer and hotter world. This is a major part of the plot, but I never quite figured out what the author describes. I didn’t understand the psychological changes that some of the protagonists went through. Because I didn’t understand the psychology, I couldn’t understand the motivations of the protagonists, especially the main one, Kerans. He seems to be partially driven by instinct and unexamined impulses.

Phantoms slid imperceptibly from nightmare to reality and back again, the terrestrial and psychic landscapes were now indistinguishable as they had been at Hiroshima and Auschwitz, Golgotha and Gomorrah.

Your residues of conscious control are the only thing holding up the dam. . . . That wasn’t a true dream Robert, but an ancient organic memory millions of years old.

The innate releasing mechanisms laid down in the cytoplasm millions of years ago have been awakened, the expanding sun and the rising temperature are driving you back down the spinal levels into the drowned seas submerged beneath the lowest layers of your unconscious, into the entirely new zone of the neuronic psyche.

Was the drowned world itself, and the mysterious quest for the south which had possessed Hardman, no more than an impulse to suicide, an unconscious acceptance of the logic of his own devolutionary descent, the ultimate neuronic synthesis of the archaeopsychic zero?

Dimly he realized that the lagoon had represented a complex of neuronic needs that were impossible to satisfy by any other means. This blunting lethargy deepened, unbroken by the violence around him, and more and more he felt like a man marooned in a time sea, hemmed in by the shifting planes of dissonant realities millions of years apart.

The ambiguous ending:

So he left the lagoon and entered the jungle again, within a few days was completely lost, following the lagoons southward through the increasing rain and heat, attacked by alligators and giant bats, a second Adam searching for the forgotten paradises of the reborn sun.

There are racist elements in the book. Was Ballard racist? I don’tknow. The gang of renegades in the novel are led by a charismatic white man. All other members of the gang who obey the leader unquestioningly are colored men described with stereotypes from the 1960s: they are all black, big, violent, uncouth, and wild. Another peculiarity of the book is that this leader can command and control the alligators.

“The Parable Of the Sower” is a chilling book because it is plausible and like what we are seeing in California and much of the world today. Heat, drought, wildfires, migration. It is a cautionary novel. We are rapidly heading toward her world unless the species homo sapiens comes to its senses and decides to save itself. “The Drowned World” is less plausible. It got the warming and rising sea levels right but to unrealistic extents. Drought is not present in “The Drowned World”. There are strange aspects in both novels. The drug pyro in Butler’s book. The psychological and evolutionary regression in Ballard’s.

** according to a 2021 study published in Physiology Report.Nov 29, 2023. From Popular Mechanics, Nov. 29, 2023