Calypso and Soca

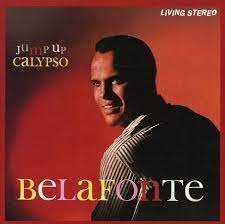

Once upon a time long, long ago when I was a teenager, most of my record buying was music from the folk revival of the 1960s. I loved the Kingston Trio, a group that was immensely popular but that now is forgotten. My other great love was Harry Belafonte, particularly his two Calypso albums, Calypso and Jump Up Calypso. Belafonte had a beautiful, mellow voice and made great music. His song “Jamaica Farewell” was the first song I liked enough to memorize.

(Scroll to the bottom if you want to skip the text and jump to some fine soca music.)

Calypso is “the most characteristic, prominent, and popular music” of Trinidad, the island from which it arose. Calypso is also sung throughout the French Caribbean where there is an Afro-French, creole culture. A West Indian diaspora brought the music and carnivals to Toronto, Notting Hill in London, and Brooklyn. New York is the center of West-Indian recording.

Columbus reached Trinidad in 1498. Before that, there were five waves of immigration from the Orinoco River basin of Venezuela, the last around 1300 CE. When Columbus arrived, there were two groupings, the Arawaks and the Caribs. The island was densely populated.

The Spaniards enslaved the population and put them to work on the cocoa, sugar, coffee, and cotton plantations. European diseases arrived, and by 1772, there remained only 417 natives. Because the plantations still needed workers, Spain’s Carlos I invited French Caribbeans to immigrate in the late 18th Century. He offered incentives; 32 acres to each white, Roman Catholic, 16 for each slave, and 16 for each free, colored person. Many immigrated from the Windward Islands to escape living in the British Empire. Unlike other Caribbean islands with plantation economies, Trinidad ended up with a large, slave-owning population of free, French-speaking coloreds.

The British took over in 1797, but the island remained mostly French and Afro-French. The music that would become Calypso was first sung in French or French Creole. After the British takeover, the lyrics were eventually written in English. Great Britain emancipated slaves throughout the British Empire in 1834-38. On Trinidad, as the now-free slaves left the plantations, the British brought in peasants from India as field laborers. By 1917, 145,000 Asian Indians had immigrated. Other new immigrants including English, Scots, and Irish arrived from British territories. Germans, Italians, Venezuelan farmers, Portuguese, Chinese, Syrians, and Yoruban Africans also arrived. Out of this diverse mix of immigrants came the kinds of music that influenced Calypso; French creole songs, songs sung by masked marchers during Carnival, neo-African genres, British ballads, the string-band music of Venezuela, creole songs from elsewhere in the Caribbean, and songs associated with stick-fighting competitions.

All these influences on top of a base of French creole produced “an easygoing natural culture that prizes humor and fun” Here is a snippet of a lyric from a song by The Mighty Sparrow.

Regardless of color, creed, or race,

Jump Up and shake your waist

An Afro-Indian, call-and-response music evolved into the solo performance of lyric verses with refrains. Calypso was performed in competitions by macho lead singers trying to outdo each other with improvised lyrics and “displays of pompous rhetoric.” The lyrics were about current events, often mocking the pretensions of the ruling classes and suggestive double entendres.

From the first, Calypso was used to criticize the upper classes. The first slaves on the island, brought from Africa to work the plantations, were denied any way to express their culture; they couldn’t even talk to each other. They used the music ancestral to Calypso to communicate and belittle their masters. After emancipation, music continued as a means of communication employed by the lower classes. Calypso was denounced by the upper classes who tried unsuccessfully to “control, co-opt, or cleanse it.” British authorities clamped down on Calypso lyrics critical of the government or that celebrated Afro-Trinidadian culture or religion. The ability of calypsonians to express popular culture was severely restricted. It was only with difficulty and courage that the restrictions could be challenged.

The musical ancestors of Calypso were performed at Carnival. At the start of the 20th Century, Carnival music split into two styles, one of which evolved into Calypso. By the 1930s, Calypso had become more standardized and commercialized. It was performed for a seated audience that cheered or heckled the singer. Calypso had lyrics as its predominant element, done by a lead singer who, until the 1970s was always male.

The first recording of Calypso was done in 1912 by Lovey’s String Band. Julian Whiterose, aka Iron Duke, recorded the first song done in English in 1914. The “style, form, and phrasing” of Calypso was solidified in the 1930s, the golden era of the music. The golden era was when calypsonians first began recording outside the Caribbean in New York.

The first artists to record outside the Caribbean moved the music into the popular mainstream. The singers that drove this popularization adopted macho names like Roaring Lion, Attila the Hun, Mighty Sparrow, and Lord Invader. Lord Invader was “one of the great calypsonians of the US.” He wrote the lyrics to and sang “Rum and Cola-Cola.” The song was made into a hit by the Andrews Sisters in 1945. Lord Invader was one of the most continuously popular calypsonians.

Another continuously popular calypsonian was The Mighty Sparrow who won the Carnival competition in 1956 and dominated the Calypso world for decades. He was an “unfailingly excellent” performer into the late 1990s. His “Banana Boat” song was popular worldwide. I couldn’t find Mighty Sparrow’s version of “Banana Boat.” Here is another of his most popular songs, “Jean & Dinah.” Belafonte recorded “Banana Boat” on his album Calypso where it (as of 03/21/2024) had 147, 610,016 listens on Spotify. Calypso was the first Calypso album to sell over one million copies. Belafonte followed Calypso five years later with Jump Up Calypso.

Calypso Rose was the first female calypsonian and won competitions with “Gimme More Tempo” and “Come Leh We Jam.” Tim Burton used Belafonte’s recording of “Jump In the Line” and “Banana Boat Song” in the movie Beetlejuice. “Under the Sea”, a Calypso tune, was used in the Disney film The Little Mermaid and won an Oscar for Best Original Song in 1973.

The message is the music, to paraphrase Marshall McLuhan, could be said of Calypso. One can’t say that it’s party or dance music. A calypsonian, Lord Shorty, and an arranger, Ed Watson, decided in the 1970s that Trinidad lacked dance music. They set out to rectify the situation and developed a genre called Soca, short for soul of calypso. Soca is “exuberant, unpretentious dance music” and party music with an uptempo, bouncy beat. It has been the main type of Calypso into the present.

Soca was taken up by calypsonians like Ras Shorty I, Mighty Sparrow, Lord Kitchener, Calypso Rose, and Super Blue. Here are a few good soca songs:

“Hot Hot Hot”, Arrow

“Pump Me Up”, Krosfyah

“Ice Cream”, Coalishun

“The Stamp”, Osha

……………..

Calypso with its lyrical orientation remains relevant but doesn’t have markets outside Trinidad and Tobago where it continues to be a main feature of Carnival. It continues to give voice to the peoples’ concerns through “social commentary or satire.”

Quotes are from “Caribbean Currents”. All other Information from:

Manuel, Peter, “Caribbean Currents: Caribbean Music from Rumba to Reggae, Revised Edition”, Chapter x, “Trinidad”, 2006

Calypso music. (2024, March 2). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Calypso_music

Trinidad. (2024, March 5). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Trinidad

History of Trinidad and Tobago. (2024, March 19). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_Trinidad_and_Tobago

Soca music. (2024, March 17). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Soca_music